The great god of flocks and shepherds among the Greeks; his name is probably connected with the verb paô. Lat. pasco, so that his name and character are perfectly in accordance with each other.

Later speculations, according to which Pan is the same as to pan, or the universe, and the god the symbol of the universe, cannot be taken into consideration here.

He is described as a son of Hermes by the daughter of Dryops (Hom. Hymn. vii. 34), by Callisto (Schol. ad Theocr. i. 3), by Oeneis or Thymbris (Apollod. i. 4. § 1; Schol. ad Theocrit. l. c.), or as the son of Hermes by Penelope, whom the god visited in the shape of a ram (Herod. ii. 145; Schol. ad Theocrit. i. 123 ; Serv. ad Aen. ii. 43), or of Penelope by Odysseus, or by all her suitors in common. (Serv. ad Virg. Georg. i. 16; Schol. ad Lycoph. 766; Schol. ad Theocrit. i. 3.)

Some again call him the son of Aether and Oeneis, or a Nereid, or a son of Uranus and Ge. (Schol. ad Theocrit. i. 123; Schol. ad Lycoph. l. c.) From his being a grandson or great grandson of Cronos, he is called Kronios. (Eurip. Rhes. 36.)

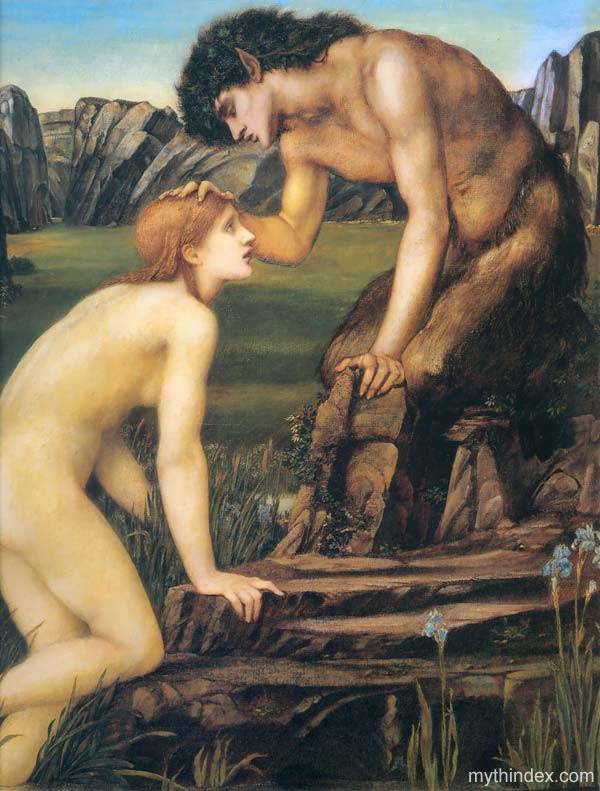

He was from his birth perfectly developed, and had the same appearance as afterwards, that is, he had his horns, beard, puck nose, tail, goats’ feet, and was covered with hair, so that his mother ran away with fear when she saw him ; but Hermes carried him into Olympus, where all (pantes) the gods were delighted with him, and especially Dionysus. (Hom. Hymn. vii. 36, &c.; comp. Sil. Ital. xiii. 332; Lucian, Dial. Deor. 22.)

He was brought up by nymphs. (Paus. viii. 30. § 2.)

The principal seat of his worship was Arcadia and from thence his name and his worship afterwards spread over other parts of Greece; and at Athens his worship was not introduced till the time of the battle of Marathon. (Paus. viii. 26. § 2; Virg. Eclog. x. 26; Pind. Frag. 63, ed. Boeckh.; Herod. ii. 145.)

In Arcadia he was the god of forests, pastures, flocks, and shepherds, and dwelt in grottoes (Eurip. Ion, 501; Ov. Met. xiv. 515), wandered on the summits of mountains and rocks, and in valleys, either amusing himself with the chase, or leading the dances of the nymphs. (Aeschyl. Pers. 448; Hom. Hymn. vii. 6, 13, 20 ; Paus. viii. 42. § 2.)

As the god of flocks, both of wild and tame animals, it was his province to increase them and guard them (Hom. Hymn. vii. 5; Paus. viii. 38. § 8; Ov. Fast. ii. 271, 277 ; Virg. Eclog. i. 33); but he was also a hunter, and hunters owed their success to him, who at the same time might prevent their being successful. (Hesych. s. v. Agreus.)

In Arcadia hunters used to scourge the statue, if they hunted in vain (Theocrit. vii. 107); during the heat of mid day he used to slumber, and was very indignant when any one disturbed him. (Theocrit. i. 16.)

As god of flocks, bees also were under his protection, as well as the coast where fishermen carried on their pursuit. (Theocrit. v. 15; Anthol. Palat. vi. 239, x. 10.) As the god of every thing connected with pastoral life, he was fond of music, and the inventor of the syrinx or shepherd’s flute, which he himself played in a masterly manner, and in which he instructed others also, such as Daphnis. (Hom. Hymn. vii. 15 ; Theocrit. i. 3; Anthol. Palat. ix. 237, x. 11; Virg. Eclog. i. 32, iv. 58; Serv. ad Virg. Eclog. v. 20.)

He is thus said to have loved the poet Pindar, and to have sung and danced his lyric songs, in return for which Pindar erected to him a sanctuary in front of his house. (Pind. Pyth. iii. 139, with the Schol.; Plut. Num. 4.) Pan, like other gods who dwelt in forests, was dreaded by travellers to whom he sometimes appeared, and whom he startled with a sudden awe or terror. (Eurip. Rhes. 36.)

Thus when Pheidippides, the Athenian, was sent to Sparta to solicit its aid against the Persians, Pan accosted him, and promised to terrify the barbarians, if the Athenians would worship him. (Herod. vi. 105 ; Paus. viii. 54. § 5, i. 28. § 4.)

He is said to have had a terrific voice (Val. Flacc. iii. 31), and by it to have frightened the Titans in their fight with the gods. (Eratosth. Catast. 27.) It seems that this feature, namely, his fondness of noise and riot, was the cause of his being considered as the minister and companion of Cybele and Dionysus. (Val. Flacc. iii. 47; Pind. Fragm. 63, ed. Boeckh; Lucian, Dial. Deor. 22.) He was at the same time believed to be possessed of prophetic powers, and to have even instructed Apollo in this art. (Apollod. i. 4. § 1.)

While roaming in his forests he fell in love with Echo, by whom or by Peitho he became the father of Iynx. His love of Syrinx, after whom he named his flute, is well known from Ovid (Met. i. 691, &c.; comp. Serv. ad Virg. Eclog. ii. 31; and about his other amours see Georg. iii. 391; Macrob. Sat. v. 22). Fir-trees were sacred to him, as the nymph Pitys, whom he loved, had been metamorphosed into that tree (Propert. i. 18. 20), and the sacrifices offered to him consisted of cows, rams, lambs, milk, and honey. (Theocrit. v. 58; Anthol. Palat. ii. 630, 697, vi. 96, 239, vii. 59.)

Sacrifices were also offered to him in common with Dionysus and the nymphs. (Paus. ii. 24. § 7; Anthol. Palat. vi. 154.) The various epithets which are given him by the poets refer either to his singular appearance, or are derived from the names of the places in which he was worshipped.

Sanctuaries and temples of this god are frequently mentioned, especially in Arcadia, as at Heraea, on the Nomian hill near Lycosura, on mount Parthenius (Paus. viii. 26. § 2, 38. § 8, 54. § 5), at Megalopolis (viii. 30. § 2, iii. 31. § 1), near Acacesium, where a perpetual fire was burning in his temple, and where at the same time there was an ancient oracle, at which the nymph Erato had been his priestess (viii. 37. § 8, &c.), at Troezene (ii. 32. § 5), on the well of Eresinus, between Argos and Tegea (ii. 24. § 7), at Sicyon ii. 10. § 2), at Oropus (i. 34. § 2), at Athens (i. 28. § 4; Herod. vi. 105), near Marathon (i. 32. in fin.), in the island of Psyttaleia (i. 36. § 2 ; Aeschyl. Pers. 448), in the Corycian grotto near mount Parnassus (x. 32. § 5), and at Homala in Thessaly. (Theocrit. vii. 103.)

The Romans identified with Pan their own god Inuus, and sometimes also Faunus. Respecting the plural (Panes) or beings with goat’s feet, see SATYRI.

In works of art Pan is represented as a voluptuous and sensual being, with horns, puck-nose, and goat’s feet, sometimes in the act of dancing, and sometimes playing on the syrinx.